Text and Photo by Grigoris A.Miliaresis

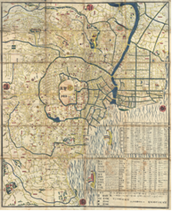

I love Tokyo’s shitamachi; I fell in love with it the first time I came to Japan as a tourist and after having spent hundreds of hours wandering around it and over a year living in the heart of Asakusa I can say with confidence that it isn’t just my favorite place in Tokyo but my favorite place in Japan. The reasons are many but if I was forced to narrow them down to one I would say it is the place where tradition seems to be so alive and vibrant; I know people usually say that for Kyoto but, perhaps because of my own shortcomings (or because I’ve only visited Kyoto a few times) I never felt it there as strong as I feel it here, the crowds of tourists notwithstanding: if the visitor is willing to walk around and stray of the beaten path of the “Holy Trinity” of Ueno Park, Sensoji and the Sky Tree (but often, even very close to it) they will find hundreds of wonderful secrets from the times of Edo, laying there for everyone to see.

The key word in the above is “Edo”: unlike many, I believe that the womb for what is fascinating in Japanese culture is the thriving capital that Tokugawa Yeasu built after his victory in Sekigahara and that became the center of Japan for over 2.5 centuries. Not only was Edo the world’s biggest metropolis before the rest of the world even comprehended the concept (in the 17th century Edo had a population of one million when the next biggest city in the world, London, had around 500.000) but it was the birthplace of one of the first urban cultures in history; that a big part of this culture is still alive today is a testimony to the spirit of the Japanese people and their unique ability to accept the new without disregarding the old or, at least, keep from the old everything that is essential. (A good example of this are the folk arts that are today synonymous with Edo but which, for the most part, were brought to the city through the constant moving of people, goods and ideas of the sankin kotai, the alternate attendance system that forced the provincial daimyo to move continuously between their hometowns and the Tokugawa shoguns’ base.) And the shitamachi, even in its present-day incarnation (which many would consider is in serious decline) is still the treasury of that culture.

“But what about martial arts?” I’m often asked by interlocutors and readers alike. “Surely someone who claims to have a long-term relation to Japanese budo must consider the Edo period (and the city itself and the culture that was developed in it) the low point in budo history. After all, it was the era when the bushi stopped fighting and became bureaucrats and when the commoners gained status leading the noble warriors of the past to decadence. How can someone who purports an interest in the martial arts be so taken with such an ‘un-martial arts’ era and its culture?” I have honestly been asked this, in several variations, from Japanese and non-Japanese alike and frankly, I think it reveals a rather superficial knowledge of Japanese history, at least as pertains to budo. Because the contrary is true: pretty much what we know as martial arts today was developed during the Edo period, both within Edo and in the provinces. And because the townspeople, the chomin, played a crucial role in its development.

These thoughts about budo and its place in the culture of Edo and its citizens came again to my mind last spring when, in a period of less than a month, I had the opportunity to attend two events, both in the shitamachi: the first one was the Oiran Dochu procession in what used to be Edo’s Yoshiwara entertainment district (and is now Senzoku, in the northern part of Asakusa) and the other the 12th Hono Enbu demonstration in the Kameido Katori Jinja, on the eastern side of the Sumida river. Even though it is less glamorous than the enbu in the Meiji Jingu, the Yasukuni Jinja or the Nipon Budokan (and it’s not sponsored by the Nihon Kobudo Kyokai or the Nipon Kobudo Shinkokai), this enbu has become a shitamachi institution and it presents visitors the opportunity to experience four arts: Tosa Eishin Ryu Iai, Yagyu Shingan-ryu Kachu Heiho, Ryushin Shouchi-ryu and Seirenkan Sosuishi-ryu; the Oiran Dochu is a newer institution but its historical ties to the area as well as the passion of present-day residents of Yoshiwara and Oku-Asakusa and the people’s attendance guarantee that it will still be around for many, many years.

The two events (as well as the firefighters’ memorial service a few weeks later -but I’ll save that for another article since the Edo hikeshi are a subject very dear to my heart) served as a reminder of how diverse Edo was and how tightly intertwined were the worlds of the bushi and the chomin. Through their present day exponents, in both cases highly invested amateurs (since the original bushi and the tayu courtesans respectively have long gone), they offer a glimpse of that multi-faceted universe where artisans, swordsmen, laborers, artists, scholars and businessmen coexisted and co-created one of the most fascinating cultures the world has ever seen. My only regret is that such events aren’t publicized much; even within Japan many people don’t know they are held and abroad they aren’t mentioned anywhere so only by chance will a visitor be able to witness them and appreciate them, the environment they are held in and the (past and present) cultural milieu they express.

The four schools featured in the enbu were an interesting mix of old and new: the Tosa Eishin-ryu goes back to the seventh generation descendant of the founder of iai, Hasegawa Chikaranosuke Hidenobu or Eishin a fascinating example of a man who lived both in a province where the goshi or countryside samurai (themselves a vague presence in the four-class system of the Tokugawa period and virtually unknown, especially in the West) had a very strong presence and in Edo thus seriously questioning the popularly held belief about who could carry a sword and practice the martial arts, the particular branch Yagyu Shingan-ryu is another art whose founder, Takenaga Hayato moved from Sendai to Edo and studied under Yagyu Munenori (another showcase of bushi and non-bushi intermingling in the great city) Ryushin Shouchi-ryu is a recent school created in the 1960s in shitamachi (its founder, Kawabata Terukata is from Taito Ward –his first dojo was in Asakusa- and its second headmaster, Yahagi Kunikazu is from Katsushika Ward) and includes iai and kenjutsu and the Sosuishi-ryu of the Seirenkan Dojo led by renowned sword polisher Usuki Yoshihiko, also based in shitamachi (Koto Ward to be precise); the school was created during the Edo times and its techniques, influenced by the Takenouchi-ryu its founder, Futagami Hannosuke Masaaki (another samurai from the provinces) studied, include kumiuchi grappling with small weapons and iai and kenjutsu collectively called “koshi no mawari”.

The enbu itself was interesting enough since I hadn’t seen any of these dojo demonstrate before; I was particularly curious to see the Ryushin Shouchi-ryu and its implementation of “traditional swordsmanship” as stated by its literature. Being a traditionalist myself I can’t say I was overwhelmed but from the post-Sengoku Jidai standpoint their technique was rather appropriate: like many styles created during the Edo and Meiji period movement was more “theatrical” (and I don’t necessarily mean that in a derogatory way), quick and with abrupt changes of direction especially in their iai; to be fair their kenjutsu kata looked more influenced by earlier swordsmanship (i.e. deeper stances, cuts to were a yoroi’s opening would have been etc.) so one could call the style a mixed bag. The Yagyu Shingan Ryu was, as always impressive, especially when -like in this enbu- they demonstrate in yoroi armor, the Tosa Eishin-ryu was pretty much as expected (as I have mentioned before I have mixed feelings for iai, especially when demonstrated as a standalone art i.e. without some accompanying kenjutsu) and the Sosuishi-ryu was perhaps the most interesting from a technical viewpoint: noticing the similarities (and differences) between it and it progenitor, the Takenouchi-ryu was fun but I would love to see more of their sword work. Perhaps at some point I need to visit Usuki sensei’s dojo!

What was more interesting though was the atmosphere. Even though the participants paid their respects to the shrine before starting and even though there was an exhibition of old yoroi right next to the stage, the whole thing gave out an air of warmth and casualness that is usually absent from these demonstrations. The stage was very close to the shrine’s outer wall and cars and people passing by made for a nice counterpoint between the old and the contemporary while the choice of the groups’ leaders to talk after each demonstration, explain (often in light tones) the techniques been performed and adding a few words about the context transformed the demonstration from something official and public to something more intimate and friendly. This coexistence of the private with the public is exactly the spirit of shitamachi, a spirit of community that is somewhat lacking from the big enbu; no surprise here since this is quite common in situations when something is organized top-down instead of bottom-up. And shitamachi culture had always been bottom-up, despite the shogunate’s attempts to rule it.

This fact of ordinary people doing (and demonstrating) arts that until some point were the privilege of the warrior class was one of the major subversions of Edo society. And it was bound to happen: in a city were hundreds of thousands of men were crowded together and were hard-working people were gradually gaining financial power and in need of distractions and pursuits other than their work (and at the same time, the ruling class was increasingly losing its “warrior” character and its economic might), there is small wonder that dojo were springing in the dozens and gathering tens, hundreds and even thousands of students -the three “Great Dojo of Edo” (Chiba Shusaku’s Genbukan, Saito Yakuro’s Rempeikan and Momonoi Shunzo’s Shigakkan) were only the top of an enormous iceberg that gave birth to the proliferation of budo that would reach its peak in the Meiji and Taisho eras.

Most people imagine the Edo society and its organization as much more rigidly stratified but such a model could only work in theory -not that the Tokugawa didn’t make an effort to actualize it but history shows that very few of the various “reforms” and attempts to impose a strict Confucian ethic actually worked (this is not to say, of course that Confucianism didn’t leave its footprint in Japanese society -it is still visible today). The melting pot that was the big city brought together the ronin and the goshi, the hatamoto and the daimyo, the artisan and the merchant and cross-pollination was bound to happen -not just from the lower classes thirsting to partake in the upper classes’ forbidden world but also from the higher classes need to balance their nominal power with one that could actually pay the bills resulted in countless exchanges or knowledge. And nowhere was this more obvious than in the Yoshiwara, Edo’s cultural center and the place where the chomin could stand next to the bushi and pursue the pleasures (carnal and spiritual) offered lavishly by the people of the “nightless city”.

Lest the reader be led astray, I’m not seeing the Yoshiwara through rose-tinted glasses when referring to it as “Edo’s cultural center”: by today’s standards it would (and probably should) be called an abomination. Judging it through modern standards though would make us guilty of presentism -phenomena must be evaluated according to the standards of the age that created them and by those standards the function of Yoshiwara was another great Edo subversion, especially considering that the coexistence of those who crossed the threshold of the Great Gate wasn’t just because they were all guided by the same sexual desire. In Yoshiwara the samurai from Aomori would learn about the Kabuki from the Kuramae rice-merchant and would reciprocate with accounts of clashes with bandits while they would both marvel at the stories recounted by the pilgrim who just returned from Ise. This exchange of information in an atmosphere wetted with alcohol, fed with the finest food and mellowed by the oiran’s songs made the people of Edo cosmopolitan without ever crossing the Sea of Japan.

Even the very fact of the existence of events like the enbu and the oiran parade today is a product of that melting procedure that happened during the Edo period and the rise of the townspeople and their mentality: it was then that the martial arts and the world of Yoshiwara managed to break the boundaries of the respective classes (the samurai and the entertainment non-class), enter the main stream of Japanese culture, and eventually become an important export of modern Japan to the world. By taking elements of these worlds and making them a part of their lifestyle, the chomin, the social force of the future, ascertained that they would not only live in the collective consciousness but that they would continue evolving.

It is hard to fathom in its full extent the legacy these two and a half centuries of cultural mingling left to modern Japanese society; events like the classic budo demonstration in Kameido Katori Jinja and the Oiran Dochu parade in Yoshiwara/Senzoku are just one small facet of this legacy. Many might see them as little more than festivities performed for the tightening of the communities’ ties (itself a very noble cause, of course) but for me they are something more and the proof lies in the fact that the exponents of the budo schools as well as the men and women performing the oiran parade are practicing constantly for these events, they get to study the details and the history related to what they do and immerse themselves into the way their present-day life relates to the life of their ancestors. These are not once-a-year societal calisthenics but lifelong pursuits offering a direct link to the past and preserving its essence for the future; that at the same time they offer the rest of us a pleasant way to spend an afternoon is just a fortunate consequence.

About the author

About the author

Grigoris Miliaresis has been practicing Japanese martial arts since 1986. He has dan grades in judo, aikido and iaido and has translated in Greek over 30 martial arts’ books including Jigoro Kano’s “Kodokan Judo”, Yagyu Munenori’s “The Life-Giving Sword”, Miyamoto Musashi’s “Book of Five Rings”, Takuan Shoho’s “The Unfettered Mind” and Donn Draeger’s “Martial Arts and Ways of Japan” trilogy. Since 2007 his practice has been exclusively in classic schools: Tenshin Buko-ryu Heiho under Ellis Amdur in Greece and Kent Sorensen in Japan and, since 2016, Ono-ha Itto-ryu under 17th headmaster Sasamori Takemi and 18th headmaster Yabuki Yuji.

http://about.me/grigorismiliaresis